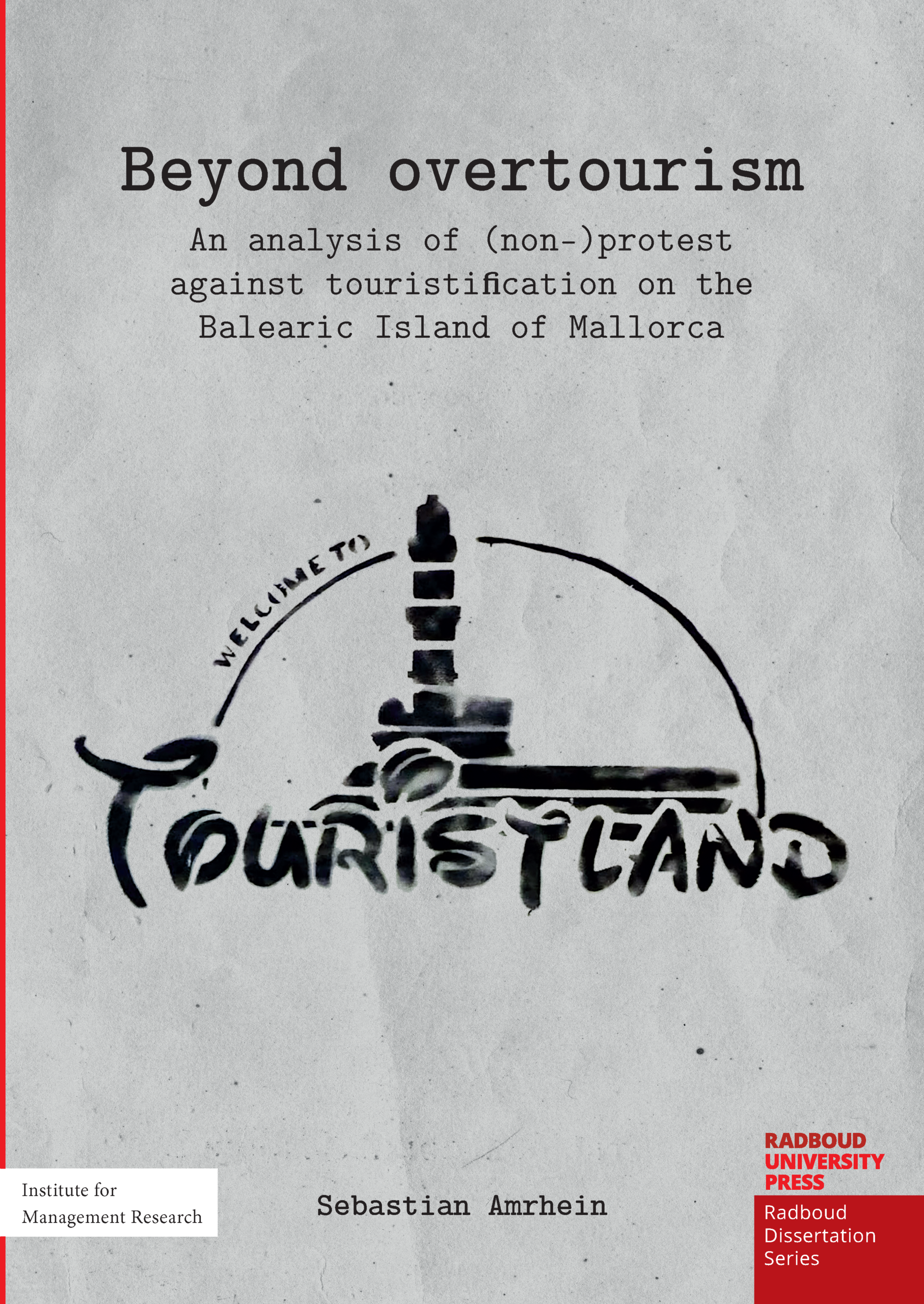

Sebastian Amrhein works as a researcher and lecturer in the Programme for Sustainable Tourism at the Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences in Kleve, Germany, just across the border, a few kilometres away from Nijmegen. He successfully defended his PhD Thesis at the Radboud University Nijmegen, entitled Beyond overtourism. An analysis of (non-)protest against touristification on the Balearic Island of Mallorca (click on cover page to download the full text) on December 16, 2025.

The main Supervisor of his PhD Thesis was Prof. Gert-Jan Hospers from Radboud University and Director of “Stad en Regio“, a foundation focused on scientific consultancy for local governmental organisations, and at the same time also Senior Researcher at the University of Ostrava, Czech Republic and Guest Professor at the Centre for Netherlands Studies at the University of Münster in Germany. With the

The main Supervisor of his PhD Thesis was Prof. Gert-Jan Hospers from Radboud University and Director of “Stad en Regio“, a foundation focused on scientific consultancy for local governmental organisations, and at the same time also Senior Researcher at the University of Ostrava, Czech Republic and Guest Professor at the Centre for Netherlands Studies at the University of Münster in Germany. With the  broad expertise and international orientation of Prof. Gert-Jan Hospers, Sebastian could not have had a better Supervisor. The co-supervisors, Prof. Dirk Reisser of Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences and I, played only a minor role. It was, however, Sebastian’s own critical approach within the field of research on overtourism which was the main driving force behind this PhD research:

broad expertise and international orientation of Prof. Gert-Jan Hospers, Sebastian could not have had a better Supervisor. The co-supervisors, Prof. Dirk Reisser of Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences and I, played only a minor role. It was, however, Sebastian’s own critical approach within the field of research on overtourism which was the main driving force behind this PhD research:

The slogan “Help – the tourists are coming,” used at a 2011 community meeting in Berlin, marked the early stages of public resistance to the increasing negative impacts of mass tourism. Since then, protests against ‘overtourism’ have expanded. In recent years, mass demonstrations in the Canary and Balearic Islands have called for a fundamental shift in the dominant growth-oriented tourism model, aligning with the principles of the degrowth movement.

The slogan “Help – the tourists are coming,” used at a 2011 community meeting in Berlin, marked the early stages of public resistance to the increasing negative impacts of mass tourism. Since then, protests against ‘overtourism’ have expanded. In recent years, mass demonstrations in the Canary and Balearic Islands have called for a fundamental shift in the dominant growth-oriented tourism model, aligning with the principles of the degrowth movement.

However, the Covid-19 crisis, in which overtourism during the lockdown was overtly not an issue anymore, also showed that tourism can not be looked at in isolation, as the fundamental societal problems behind overtourism still remained. Overtourism, therefore, is not just an issue of ‘managing tourism’ but needs to be analysed from a broader societal perspective.

Sebastian Amrhein critically examined the potential for transformation within global tourism by analysing the sector through the lens of these more fundamental power structures and social inequalities, from the perspective of degrowth theory. Structured around three interrelated sub-projects, the research explores how overtourism impacts residents, why many do not engage in protest despite dissatisfaction, and whether local initiatives like Cittaslow can serve as viable degrowth placemaking strategies.

The first sub-project investigates whether overtourism can lead to fundamental shifts in residents’ worldviews. Drawing on Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory (1997), the study finds that overtourism can indeed lead to profound personal transformation, particularly among older individuals who have witnessed long-term changes in their environment. For them, experiences of environmental degradation, overcrowding, and social disruption led to a reassessment of tourism and capitalist economic models. Conversely, younger individuals lacked a comparative baseline and viewed these conditions as normal, often expressing disengagement or negative views of tourism without undergoing a transformative shift. The concept of shifting baselines is introduced to explain generational differences in perception, highlighting the importance of lived experience and memory in shaping critical awareness.

The second sub-project explores why many residents refrain from participating in protests against overtourism. Sebastian Amrhein identified structural inequalities, economic dependency, and social habitus as key barriers to activism. Many respondents, particularly those from lower socio-economic classes or informal tourism employment, feared social exclusion, economic loss, or lacked awareness of the movements altogether. In contrast, protest participants were largely from the middle class, with prior experience in activism. The study applies Bourdieu’s theory of practice (2013) to demonstrate how social position and cultural capital shape individuals’ capacity and willingness to engage in political action. Misinformation and media narratives were also shown to influence public perception, often delegitimising protest movements by framing them as irrational or xenophobic. This supports the claim that discursive power is used by dominant actors to maintain the status quo.

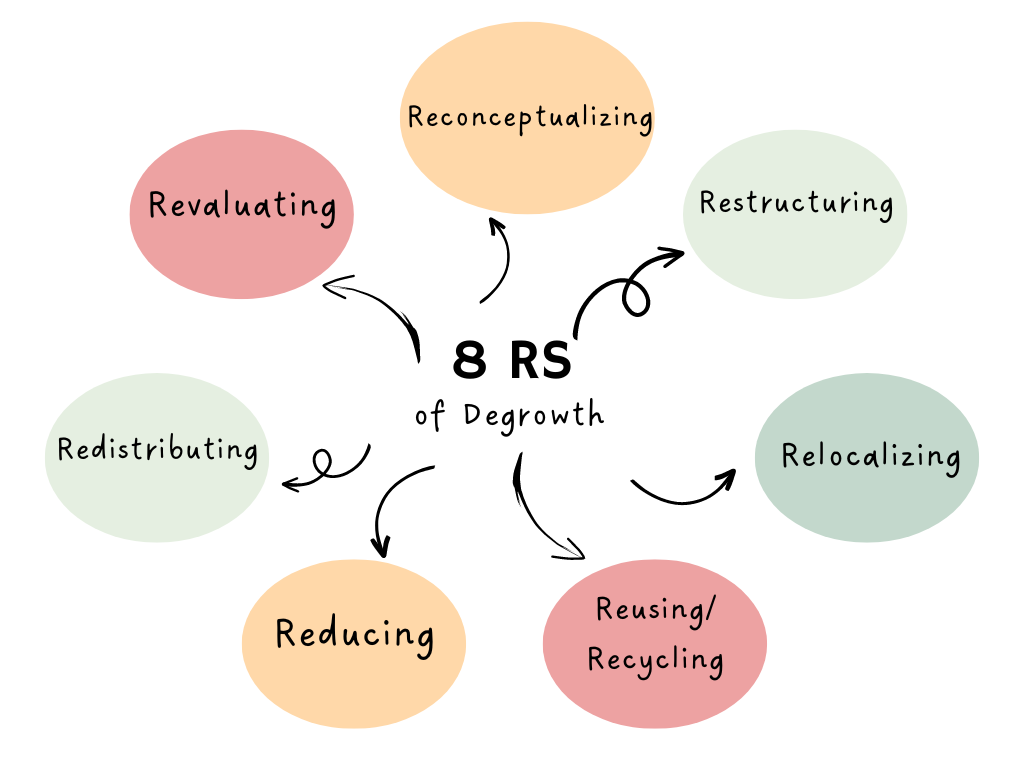

In a third sub-project Sebastian Amrhein analyses Cittaslow as a potential degrowth initiative. By comparing Cittaslow’s principles with Latouche’s eight Rs of degrowth (2009) and conducting a case study in Artà, Mallorca, he found significant conceptual overlap but also notable differences. While Cittaslow emphasises local well-being, sustainability, and cultural preservation, it lacks the radical critique of economic structures central to degrowth. Its open-ended nature allows for both promotional and transformative interpretations, depending on local political will. The study highlights the flexibility of Cittaslow as a strength but also a risk, as its impact is contingent on leadership priorities rather than embedded systemic change. Furthermore, both Cittaslow and degrowth lack detailed implementation guidelines, complicating their translation into effective policy.

In a third sub-project Sebastian Amrhein analyses Cittaslow as a potential degrowth initiative. By comparing Cittaslow’s principles with Latouche’s eight Rs of degrowth (2009) and conducting a case study in Artà, Mallorca, he found significant conceptual overlap but also notable differences. While Cittaslow emphasises local well-being, sustainability, and cultural preservation, it lacks the radical critique of economic structures central to degrowth. Its open-ended nature allows for both promotional and transformative interpretations, depending on local political will. The study highlights the flexibility of Cittaslow as a strength but also a risk, as its impact is contingent on leadership priorities rather than embedded systemic change. Furthermore, both Cittaslow and degrowth lack detailed implementation guidelines, complicating their translation into effective policy.

Across all three sub-projects, the thesis challenges simplified narratives in tourism research, particularly the assumption that economic benefit equates to support for tourism. It reveals that tourism’s impacts are deeply interwoven with broader social dynamics and that resistance or acceptance is shaped by class, dependency, generational experience, and access to discourse. The findings call for a more nuanced, critical, and justice-oriented approach in tourism studies, one that moves beyond economic metrics to consider power relations and transformative possibilities.

Across all three sub-projects, the thesis challenges simplified narratives in tourism research, particularly the assumption that economic benefit equates to support for tourism. It reveals that tourism’s impacts are deeply interwoven with broader social dynamics and that resistance or acceptance is shaped by class, dependency, generational experience, and access to discourse. The findings call for a more nuanced, critical, and justice-oriented approach in tourism studies, one that moves beyond economic metrics to consider power relations and transformative possibilities.

Ultimately, Sebastian Amrhein could confirm that tourism is not merely a sector to be managed but a social field that both reflects and reinforces existing inequalities. Meaningful transformation, therefore, requires more than local initiatives; it demands structural critique, inclusive discourse, and the political will to reimagine development beyond growth.

References

Bourdieu, P. (2013) Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Latouche, S. (2009) Farewell to growth. Polity Press, Cambridge.

Mezirow, J. (1997) Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. No. 74, pp. 5-12.