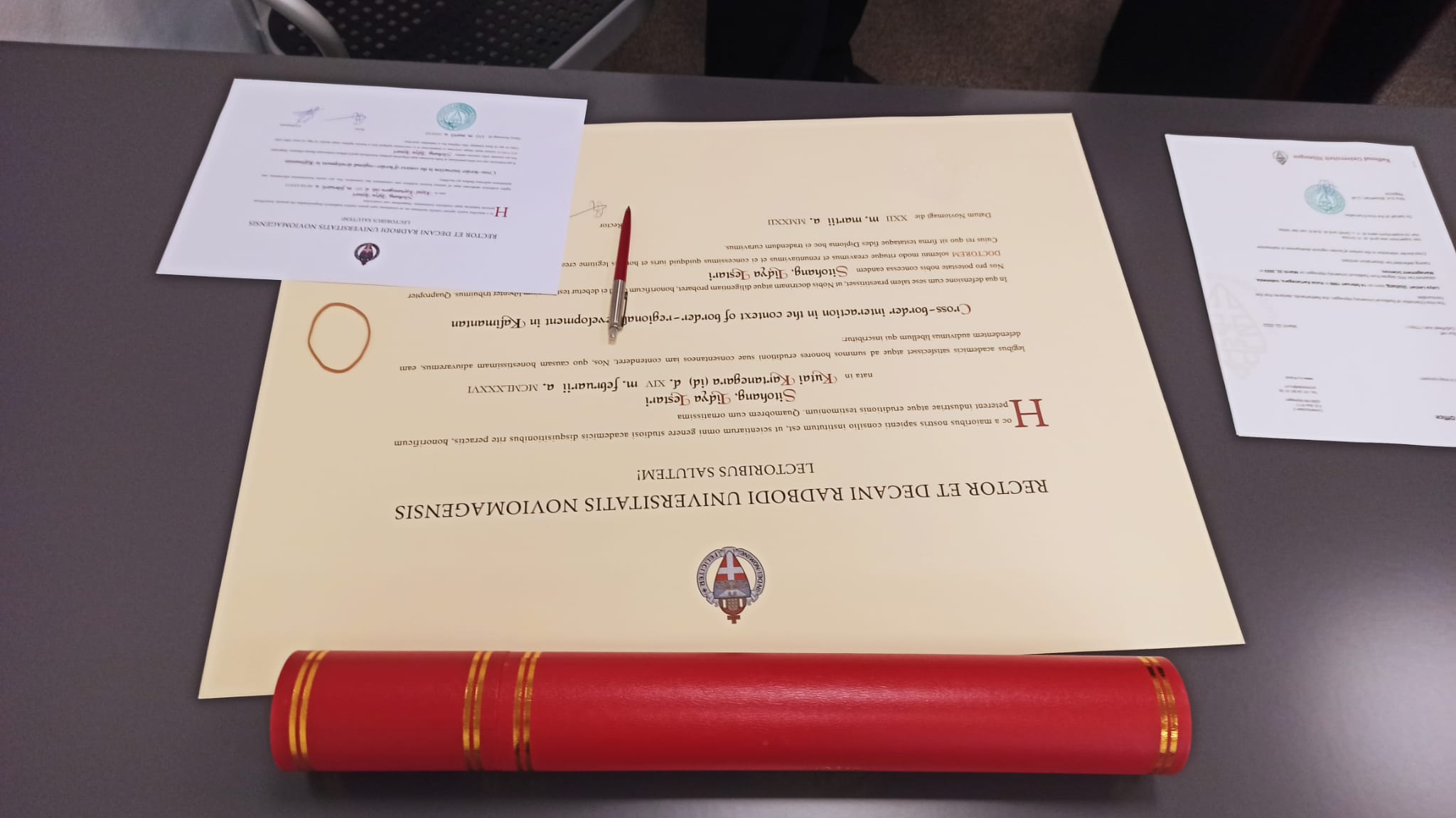

On Monday, Nov. 24, 2025, Veronica Pastorino successfully defended her PhD Thesis entitled: “Spatial Citizenship. Understanding the challenges and redefinitions of contemporary social cohesion through the analysis of the geographies of post-migrant contentious politics” (click on cover page to download full text). Through this defence, she did not just earn the PhD title from the Radboud University in Nijmegen, but also from the University of Bologna, as part of the Double Degree Programme between both Universities.

On Monday, Nov. 24, 2025, Veronica Pastorino successfully defended her PhD Thesis entitled: “Spatial Citizenship. Understanding the challenges and redefinitions of contemporary social cohesion through the analysis of the geographies of post-migrant contentious politics” (click on cover page to download full text). Through this defence, she did not just earn the PhD title from the Radboud University in Nijmegen, but also from the University of Bologna, as part of the Double Degree Programme between both Universities.

The long title of this PhD thesis reflects the ambitious and complex setup of the underlying PhD research, which might need some clarification:

The PhD Thesis focuses on how second-generation youngsters with a migration background, also called ‘migrants’ descendants’, gain citizenship in their new home country.  Following the seminal work of the Citizenship scholar Engin Isin, Veronica suggests that this is much more than just a formality. It is not so much related to their judicial status, although,that is of course also part of it, but more related to becoming a full-fledged member of the host society and community, as well as to how others recognise them as such. It is much more a multiscalar ‘practice’ and a ‘process’. Citizenship emerges out of what political actors and ‘citizens’ do… This already makes it clear that it is not just an issue of nationality or of the nation-state, but also of the local and regional communities in which they are active. This brings in the dimension of space (or place). Identification with and belonging to a specific place can occur at different spatial scale levels. The way one might gain this kind of ‘citizenship’ can also vary from one place to another.

Following the seminal work of the Citizenship scholar Engin Isin, Veronica suggests that this is much more than just a formality. It is not so much related to their judicial status, although,that is of course also part of it, but more related to becoming a full-fledged member of the host society and community, as well as to how others recognise them as such. It is much more a multiscalar ‘practice’ and a ‘process’. Citizenship emerges out of what political actors and ‘citizens’ do… This already makes it clear that it is not just an issue of nationality or of the nation-state, but also of the local and regional communities in which they are active. This brings in the dimension of space (or place). Identification with and belonging to a specific place can occur at different spatial scale levels. The way one might gain this kind of ‘citizenship’ can also vary from one place to another.

Veronica investigated the processes of how these youngsters gain citizenship in their new home surroundings in two different countries, Germany and Italy. In both countries, she looked at specific social movements, or one could roughly also say: specific ‘NGO’s’, which intend to support these youngsters in gaining citizenship. These social movements in both countries operate on a national as well as on a regional/local level, reflecting also the different spatial scale levels of identification, belonging and (social) cohesion.

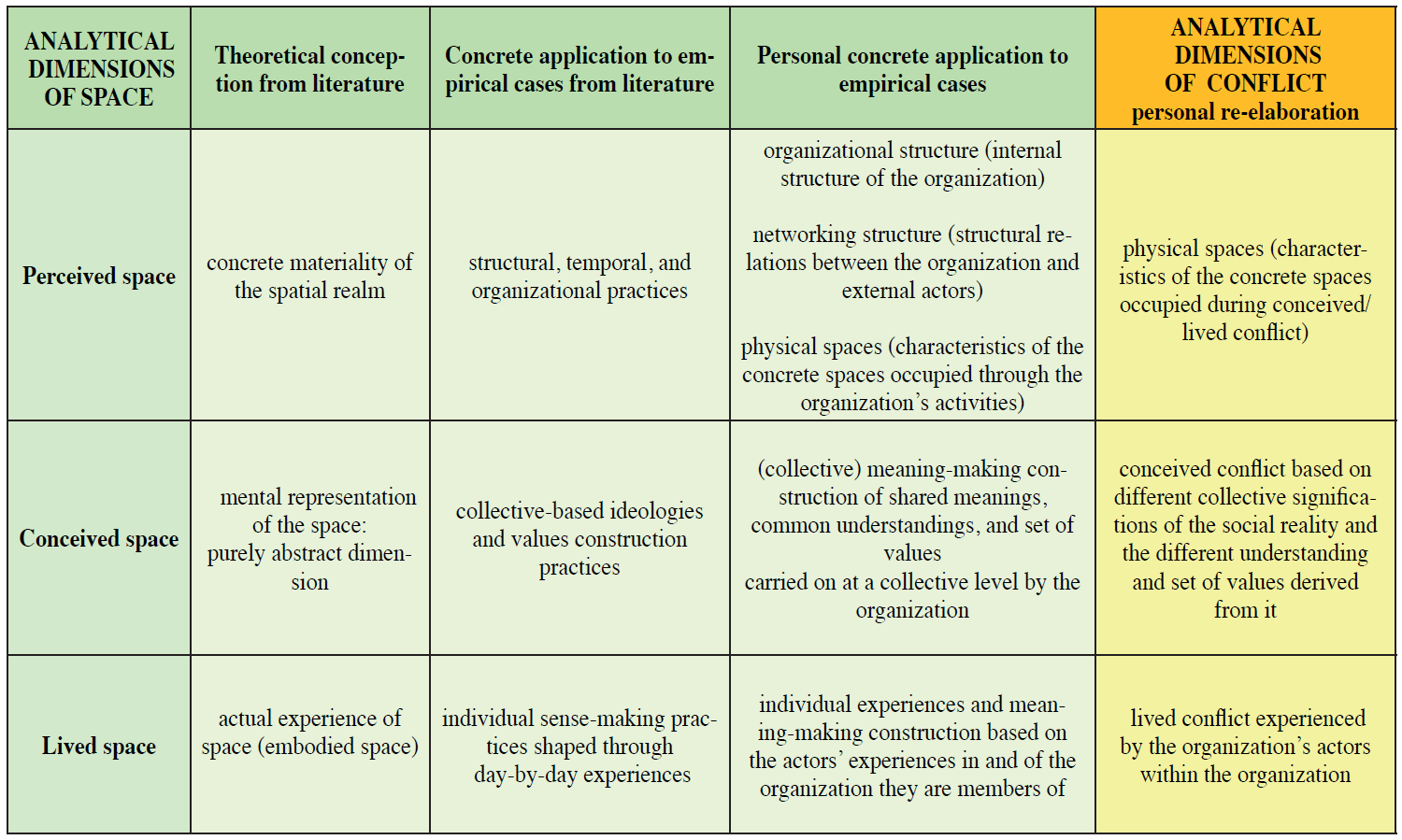

To conceptualise the complex spatiality of these processes, Veronica adopts and adapts the triad coined by Henri Lefebvre comprising Perceived Space (the more material and physical characteristics of space), Conceived Space (the conceptual and mental transposition of space) and Lived Space (the embodied and personally experienced aspects of space).

To conceptualise the complex spatiality of these processes, Veronica adopts and adapts the triad coined by Henri Lefebvre comprising Perceived Space (the more material and physical characteristics of space), Conceived Space (the conceptual and mental transposition of space) and Lived Space (the embodied and personally experienced aspects of space).

So Veronica tried to grasp the complexity of gaining citizenship based on individual and social actions, as well as on the individual and collective activities of these different social movements operating in different national and societal and political contexts.

Gaining citizenship is not an easy thing, and goes along with resistance and conflict and therefore can be described as a real ‘struggle’. This also demands critical reflection on how this actually takes place and might be improved. If it utterly looks as if it occurs smoothly and peacefully, there would be no reason to seek alternative ways of dealing with it, even though the underlying problems might still be there. Veronica, therefore, also concludes that some degree of irritation and conflict is actually needed to make critical reflection on these processes and ‘learning’ from errors effective.

Gaining citizenship is not an easy thing, and goes along with resistance and conflict and therefore can be described as a real ‘struggle’. This also demands critical reflection on how this actually takes place and might be improved. If it utterly looks as if it occurs smoothly and peacefully, there would be no reason to seek alternative ways of dealing with it, even though the underlying problems might still be there. Veronica, therefore, also concludes that some degree of irritation and conflict is actually needed to make critical reflection on these processes and ‘learning’ from errors effective.

In this way, her research attempts to contribute to societal and political debates as well as to scientific debates in the fields of European Postmigration Studies, Social Movement Studies and Citizenship Studies by adding a critical spatial lens to it.

In this way, her research attempts to contribute to societal and political debates as well as to scientific debates in the fields of European Postmigration Studies, Social Movement Studies and Citizenship Studies by adding a critical spatial lens to it.